It has been a while since I posted anything. I have been busy but more than anything else it’s discouraging not having any actual comments on the website itself. I must be doing something wrong. Anyway, this post is for any of you who have children, grands, nieces or nephews or kid friends you want to encourage to write some poems of their own.

Of course poems don’t have to rhyme. A poem is an instance of attention, of noticing something in the world others don’t see that you would like to show them. If you succeed in having them see what you do then you have written a good poem. here is an example:

Stop. Just stop. No texting, no talking, no fidgeting.

Look, take a look around you.

Look at what you are not seeing.

Like when you were at that restaurant

where the little girl,

about three,

was unselfconsciously

figuring out

how to eat a piece of toast without letting the jelly fall off or stick to her fingers

as though

it

was the

only

thing

in

the world.

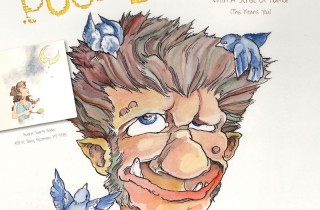

Most kids like to hear and recite poems that rhyme; that’s why they love limericks like the ones in my book. “Little Bo Peep” and other traditional poems have this form. You can work with kids and easily work out the rhyme scheme with them. Another way to start is to play lots of word rhyming games with them and have fun simply saying a lot of silly things. If they have a friend named Bryce ask if he eats rice and repeats everything twice. They need to answer in rhyme and say, no, but he’s very nice. If he’s named Pete, does he eat meat? No, but he has smelly feet. Ask if Olivia is from Bolivia and, if you ask, what will she give ya. If you don’t have a rhyme for a name like Charley you can ask if he’s nice and is covered with lice. The answer just has to rhyme like, No, he’s tall and can’t play ball. The easiest rhyming poems to start with are ones that use words that match perfectly. And example is the first poem in my children’s book about little Willy. You can easily write silly poems with words which have identical end rhyme, the last vowel and consonant are the same. Rather than try and figure out or remember all the words that can rhyme for your poem there is a great book you can get that your kids will love. Get The Penguin Rhyming Dictionary by Rosalind Fergusson. Try writing a poems using all the words that rhyme with bees for example. Start by writing down all the words that rhyme and you will soon have bees stinging your knees as you try to eat cheese under the trees. But then a huge sneeze might frighten the bees away from the trees and you could end up with a disease that would make you wheeze because some of the bites were not from bees but from anopheles( a type of mosquito). I’ll leave you with one of these identical end rhyme poems that has proved popular with the children who have attended some of my presentations. The poem ends the way it does because the poem about little Willy in my book starts out “Sometimes it’s a crime when all the words rhyme”. Once after I read it to some kids they said I should go to jail! I am going to write it here in a paragraph form so I don’t have a long string of over thirty verses.

MATT AND HIS FAT CAT THAT SAT ON A RAT: A boy I know named Matt always wanted to chat about his cat and how it once caught a rat. But no one could believe that once they saw his cat because it was incredibly fat. It was far too fat to catch a rat and it just sat and sat on its big fat prat.One day this unbelievably fat cat accidentally sat on a rat, a very dumb, slow rat who was trying to steal his food and squashed him flat. So flat that Matt wanted to use him for a fishing hat. But his mom objected to that. Matt could be a bit of a brat so he put the rat in front of the door for a mat. His mom also said no to that. So he decided to use it for a Frisbee. It was gross to see that flying rat because when you caught it it went SPLAT! Unless you could grab it by the tail. Oh no! I have to go to jail. I’ve committed the crime of making a poem with perfect rhyme. I couldn’t help it!